The Baby is Dead, but Other Tragedies Feel More Real

Before we dive in, let me just say—whether you believe me or not—not all of this post is ripped from my personal diary. Sure, some of it is. But other parts are stitched together from what I imagine countless other parents are quietly grappling with.

The Perfect Nanny doesn’t just tell a story, it flings open the closet doors and shines a light on the dark, unspoken truths of parenthood. The ones we’re not supposed to say out loud. The ones we package in polite smiles and Instagram captions.

I’m not here to confess which parts are mine. That’s not the point of this (obnoxiously long) post. Instead, I’m here to walk through the many valid, completely normal emotions that surface when you lose yourself to parenthood.

Before we dive into this review, a couple housekeeping notes from your resident Illiterate: First, juggling two book clubs has gone about as well as expected—which is to say, terribly. I haven’t touched a short story in weeks. Tragic, I know. But the real tragedy? I just finished a novel that begins and ends with dead children. Not a metaphor. Actual dead kids.

On the bright side, I did manage to finish The Perfect Nanny, the book I personally selected—so no Four Horsemen shot for me this time (small mercies). Even better, my once-disgraced friend who recommended The Ministry of Time (see: previous blog rants) may have just clawed her way back into literary redemption.

So, let’s get into this review… with a healthy detour into my very not-humble thoughts on parenting—an area where, it turns out, author Leila Slimani and I might just be soulmates.

The Perfect Nanny opens with this little charmer: “The baby is dead.” Hell of a hook, right? My immediate reaction, aside from a whispered “Jesus Christ, was wondering if I had just signed myself up for 200+ pages of child death. Thankfully, no. A quick narrative pivot takes us somewhere only slightly less soul-crushing: the slow, grinding despair of modern parenthood.

Now, before I take the promised off-ramp into my own opinions on that cheerful topic, let me pause to say: I honestly don’t know if Leila Slimani meant to run two parallel plots here (dead baby plus the existential horror of parenting), or if she just decided to bait us with an anvil to the face and then pivot to the quieter tragedy of daily life with children. If it was the former—dual track storytelling—I don’t think it fully landed. But if it was the latter—shock and switch, then she mostly nailed it.

If I ever bump into her at a café, I’ll ask. And you can bet I’ll blog about it.

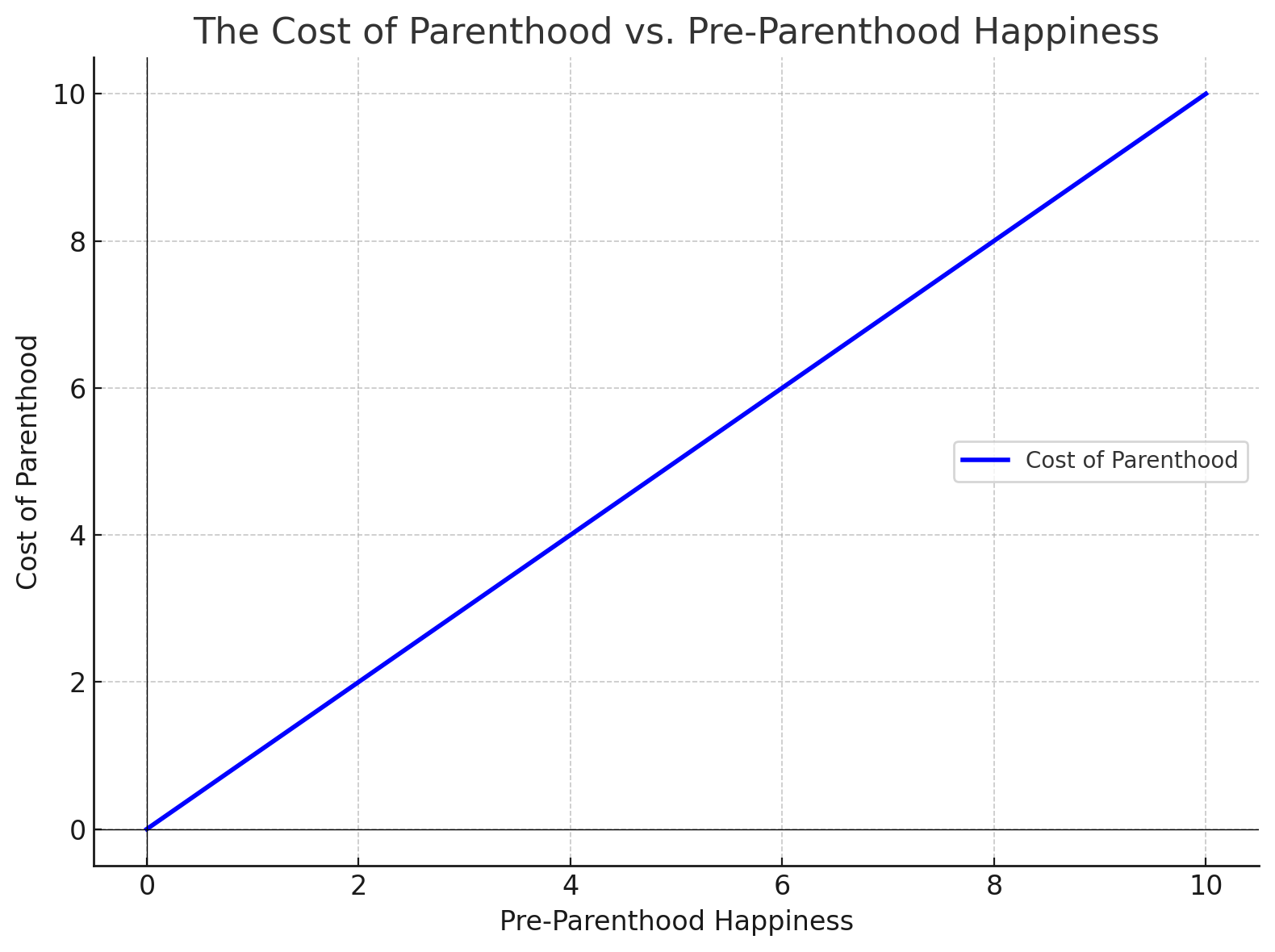

Alright, Illiterate Controversial Statement #1. Parenthood comes at a cost. And that cost isn’t just measured in diapers and daycare bills—it’s paid in personal freedom, sleep, leisure, patience for your partner, and, yes, happiness. I said it. Happiness. Parenthood is not synonymous with it. (Gasp!) In fact, it often feels like the exact opposite. Sure, there are benefits—I’m not denying the occasional heart-melting moment—but they come with a very real, very tangible price tag. Ask any parent. They know.

Here’s the brutal math of it: the happier you are going into parenthood, the higher the cost of becoming a parent. If your pre-kid life was full of deep conversations, frequent sex, satisfying work, spontaneous trips, or just the luxury of doing nothing… parenthood is going to feel like an anvil dropped squarely on your chest because you're likely to lose all, or nearly all, of the above. On the other hand, if your life pre-kid was already a bit of a void—meh marriage, meh job, meh fun—then there’s not much joy to displace. Lower baseline, lower cost.

It's not exactly Hallmark, but it's honest.

And this, dear friends. my literate, possibly childless readers, is exactly where the mother (and later, the father) go horribly, tragically wrong. These two were clearly thriving pre-children. They had it. Not the flimsy, performative nonsense of the American Dream, but the real deal. Something purer. They had happiness.

The kind of deeply satisfying, borderline narcissistic happiness that only becomes obvious in its perfection after it’s been obliterated by children. The kind where your life is your own, and that turns out to be more than enough.

Her brief stint as a stay-at-home mom doesn’t just wear on her—it erodes her and quickly. She becomes a shell of who she once was. A duller version. A drained version. A woman who once argued cases now struggles to finish a sentence without a yawn.The dream of parenthood, the “awww” moments, the Instagram-worthy milestones—gets steamrolled pretty quickly after that whole “the baby is dead” opener. And what follows, through the eyes of the intelligent, undoubtedly beautiful, high-achieving attorney-turned-mom, says it all: the boredom, the loss of identity, the eerie hollowness of having nothing remotely interesting to say when asked, “How was your day?” You can literally feel the sex between the couple dissipating as the words spill off the page.

Which brings me to Illiterate Controversial Statement #2: Parenthood isn’t just boring—it makes you boring. It has to. You simply don’t have the time or energy to be anything else.

Let’s start with the first part: parenting is boring. Painfully so. Any parent trying to convince you otherwise is either lying to you or lying to themselves (or both). And how do I know? Easy. Here’s the test: take the kid out of the equation. Now ask that same parent—would you, of your own volition, watch The Lion King for the tenth time this month? Would you choose to spend your Saturday sitting on a park bench watching any other toddler eat sand again? Would you read that damn toddler book every night one time, let alone every night, for a year?

Of course not. No sane adult signs up for that in a vacuum. The objective truth is: by any reasonable standard, it’s boring. And that’s just the reality, no matter how many whimsical filters you slap on it.

Now let’s talk about the second part: how parenthood makes you boring.

As you’ve probably guessed by now, I’m a parent (and a pretty damn good one, if I may say so). But I used to be more than that. I used to be interesting. Like, genuinely interesting, not in the humblebrag way, just in the “I had a lot going on” way. I had enough passions and curiosities to hold my own in just about any conversation. People liked talking to me because I had things to say. I used to pull all-nighters chatting with my spouse, gaming, debating sports, trading music recommendations, writing code for fun. My interests weren’t just hobbies, they literally defined me. They shaped how I moved through the world.

Now? Not so much.

I’ve lost the time to stay sharp. The energy to stay curious. The patience to be socially graceful. Most of what made me me has been chipped away by the slow, relentless erosion of parenthood.

Because let’s be honest: how the hell is anyone supposed to stay interesting when, for a solid decade, 98% of your so-called “free” time is spent cleaning up shit (both literal and metaphorical), reading toddler books, watching toddler movies, and teaching basic math to a tiny human who doesn’t care if you once had nuanced opinions on the rise and fall of indie rock?

Short answer: you can’t.

And so, like every other good parent I know, I say it plainly: I’m boring.

Which brings us to the next truth bomb tucked inside this deceptively cheery little book: Mom and Dad genuinely believed they could do parenthood without changing a damn thing. That they’d keep their friends. Keep their passions. Keep the fire between them alive. That they wouldn’t become boring.

Right around page 100 we see this through dad's eyes. There’s this brief, almost sweet moment where he seems to believe he can have it all, travel, be interesting, stay in love, raise a kid, without having to change. That fantasy lasts about a paragraph before reality T-bones him like an 18-wheeler. Parenthood doesn’t let anyone off the hook. Not even the idealistic, “progressive” dad who thinks he's different.

It’s laughable in hindsight—pure delusion through a post-kid lens—but in the moment? They believed it. Fully.

And here’s the kicker: it’s only when they pay someone else to take the kids out of the equation that they begin to resemble their former selves. That’s the whole tragic arc of the book. The big, overarching premise is that happiness—their happiness—only returns when someone else absorbs the cost of parenthood.

The nanny wasn’t just there to help. She was the escape hatch. The only thing standing between their old selves and the slow death of who they’d become.

This anvil, this punch to the face, this swift kick to the soul (or wherever you store your dreams), hits even harder when someone strolls into parenthood thinking, “I can have kids and not change a goddamn thing.” Spoiler: you absolutely cannot. I at least was fortunate to not expect this. I anticipated the real moments of misery and boy oh boy, did it deliver.

Like the saying goes, you can’t have your cake and eat it too, and when it comes to parenting, that cake gets tossed out the window the moment the baby arrives. It is flat-out impossible to be a good parent without dramatically overhauling your entire way of life. You don’t “fit” a child into your routine. You gut-renovate the routine. Whatever your lifestyle was before? Kiss a good chunk of it goodbye. Or I guess, for Mom and Dad in the book, the equation is even simpler: you pay someone else to lift the burden, so you can reclaim whatever scraps of your former glory still remain. The nanny isn’t just childcare. She’s a lifeline to the people they used to be before parenting steamrolled their identities.

To raise a kid well, you have to give up a significant part of who you were. At times, it even feels like you’re giving up all of who you are. That’s not dramatic, it’s just the deal. So, yeah. Deal with it.

And then we hit the real taboo, the one no parent’s supposed to admit out loud. As if everything before this wasn’t already a social faux pas. I’m talking about the fantasy of escape.

These fantasies wear different faces. For Dad, it’s retreating into work, into silence, into the sweet, numbing absence of need—no kids, no partner, just solitude. For Mom, she flees back to being an attorney, and, it feels like there's at least moments of sexual tension between her and her boss/law school friend. A longing for passion, for being wanted—by someone who doesn’t scream “Mommy” with peanut butter on their face.

In a subtle role reversal, the man prepares to vanish into nothingness, while the woman might ache for someone else. But beneath it all, they’re chasing the same thing: to feel anything other than the constant pull of parenting.

It’s the secret dream every parent toys with late at night, that maybe, just maybe, you could run from the crushing weight of domestic life… and come back to find everything still in place.

The worst part of this is that the fantasies, rarely, if ever, include the other parent. This is on display in a devastating way in the book through the fantasy of the Nanny, and the reality of mom and dad. She believes if she takes the kids for the night, the parents will spend the evening fucking, rekindling passion, sipping wine and whispering secrets. But reality? They’re arguing, or bored, or escaping into separate corners of the house, just trying to survive another day. Moments together aren't filled with fantasies, they're filled with chores, sleep, or the kind of silence that screams.

The author brings this point home perfectly when the nanny drops the kids off and sees the parents’ real night. The dad is lying on the couch, listening to a record. The mom? She showered, went to bed. They barely speak. A point the author makes sure to expressly state. That’s it. That’s the big romantic night. And the nanny is devastated — just like every naive, soon-to-be parent will one day be when they realize this is what it becomes.

Not a disaster. Not a tragedy. Just the slow erosion of intimacy, buried under fatigue and the mundane repetition of survival.

The nanny’s version of this family like our friends’ perfect posts on Instagram and Facebook, is a lie. A curated fantasy, as implausible as those of mom and dad.

So where does this leave us. A book that starts, and ends, with dead kids, but in between, a deeply troubling view of parenthood's warts. The book tries so hard to be about the nanny. To tie everything back to her. And sure, maybe it’s all “intertwined,” but sometimes it feels like Slimani wants the murders to be the story — when they’re not. The real story, the one that hurts, is the parents. Two people dissolving in slow motion. The crime is just the hook.

This novel could’ve stood tall without any deaths at all, just a raw, brutal portrait of how parenting hollows people out. As, frankly, most good parents know all too well.

And on that note, I'll end this one, a little sad about the facts, a little relieved to have written it all out.